Legal access to medical marijuana has been increasing in Canada in recent years. Court decisions and regulatory changes have set the course, which has not always been a direct route.

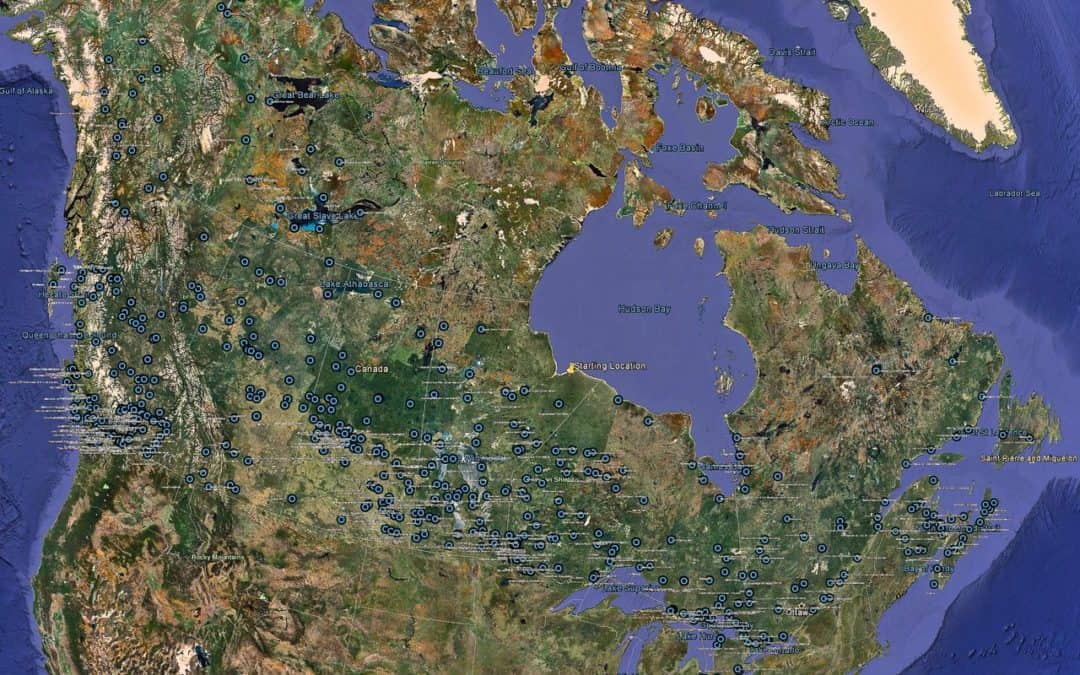

The most current published data from Health Canada confirms the trend of greater access. In 2009 about 4,000 individuals had obtained authorization to possess in Canada (CMA Policy: Medical Marijuana; citing Statistics Canada Health Canada: Marijuana for Medical Purposes, June 5, 2009). In 2013, active authorizations to possess were at 38,500 in Canada (Health Canada (2013) Marihuana for Medical Purposes).

Of note, the trends in prescription have not been distributed evenly across each province. To demonstrate, refer to the above comparative graph of the percentage of the population by province with authorization to possess medical marijuana. When interpreting the chart above it is also useful to know that a permit to possess issued by Health Canada is tied to a declared place of residence and workers often maintain a residence in one province and work in another. So the place of residence and place of work are both relevant in examining this Health Canada data. For example, Alberta hosted anywhere from 60,000-120,000 workers each year from 2004 to 2010, according to Statistics Canada and so some number of permits to possess issued in other parts of Canada could make their way to Alberta workplaces.

Prescription marijuana cases push Labour Relations practitioners immediately into that balancing act between obligations arising from Human Rights and Privacy Rights legislation, versus competing obligations pursuant to Occupational Health and Safety legislation. If you have not encountered the situation it is becoming more likely that you will. One of our Practitioners recently recruited 2000 skilled tradespeople in British Columbia. If the distribution was normally distributed we would expect 80 medical marijuana files (extrapolating from the chart above). Clearly, that is not the case. Many of those treated via medical marijuana would be managing conditions that would prevent them from fulfilling the physical demands of safety-sensitive positions in the construction industry. Anecdotally, however, one of our practitioners:

- is aware of two(2) cases in Alberta in 2009, encountered his first (1) file directly in 2010 while managing six sites across Canada, and;

- more recently, encountered four (4) files in one year (2013-2014) in British Columbia on the same site.

With social and legal trends toward increased medical use and full legalization continuing, the acceptance and prevalence of medical marijuana in the workplace is only likely to rise. But it is difficult to gauge the pace of change as there is no known data on cases of prescription marijuana entering the workplace. Of course, full legalization does not mean it is permitted to be used in the workplace, but full legalization is likely to contribute to increased acceptance of medical use and turning up in your recruitment process and workplace.

Questions to ask when a prescription collides with the requirements of a safety-sensitive position

So when a medical marijuana prescription finds its way to your workplace, what do you do? One approach is to separate the three main labour relations concerns.

- First is the legality of marijuana in a worker’s possession when the marijuana’s source or form does not match the prescription or when it’s in the possession of a worker without any prescription at all.

- Second, all of the health and safety concerns that flow from marijuana being on a worksite including concerns that extend beyond the individual with the prescription.

- And third, the potential workplace impairment of the individual worker.

The initial questioning from a front-line Labour Relations Officer concerned with health and safety risks to staff and the legality of possession should cover the following:

- Does the worker have a permit to possess marijuana from Health Canada? Request a copy of the permit to possess issued to the individual if they are going to possibly be carrying on a worksite or company property. A prescription to consume marijuana is a different legal matter than the right to possess marijuana.

- How is the worker obtaining the marijuana?

- Does the worker have marijuana with them now or at the site?

- Where is the worker keeping the marijuana while they are working, when they are commuting to work, or while residing on project-supplied accommodation?

- Did the worker get searched or questioned by site security or airport security (in cases of a fly-in-fly-out work arrangement)?

- If the marijuana was not transported from home then how was the marijuana obtained? From a co-worker or on the work site?

These questions focus on the source of supply for the worker, and this line of inquiry can lead you to related issues that need to be addressed in order to maintain workplace safety. If the source is on site, an investigation into who, when and where will be necessary. For contractors doing business on a project site, this may involve coordination with security, site owners and other contractors on site.

- Does the form of the drug (dried plant, liquid, pill, etc) possessed by the worker match what is stated in the prescription?

- Does the form of the drug (dried plant, liquid, pill, etc.) possessed by the worker match what is stated in the prescription?

These steps should ensure the medication and items related to consumption match the prescription held by the worker. Moving on to concerns of potential impairment of the worker, a Labour Relations Officer should explore the following:

What restrictions have been provided by the doctor? Obtain the prescribing doctor’s direction on dosage, timing, a form of the drug, work restrictions and safety precautions. Like any prescribed medication, a doctor should have provided instructions on how to take the prescription and the limitations on the user when they are under the influence of the medication. It is not uncommon that employers need to seek more detailed information from the prescribing doctor. It is key to provide a full and detailed description of the job and site on which it is performed so that the doctor can provide informed direction.

Once initial information gathering from the employee is complete, it would be wise to seek your own medical expert and have them enquire on the following points with the prescribing doctor:

- How was the dosage in the prescription determined? How long has the worker been a patient of the prescribing doctor?

- Is the worker under any other doctor’s care for the condition for which the marijuana was prescribed?

- How many other doctors have the worker visited in the past year?

- Why were the form of the drug and the timing of the dosage prescribed as it was?

- Is there any flexibility as to the form of the drug or the timing of consumption?

- Is the form of the drug and method of consumption specified in the prescription?

- Are other forms of the drug or methods of consumption acceptable according to the prescription?

Using a medical expert to explore these questions may reduce risk related to when and how the drug is consumed or the form of the drug that may be brought onto the worksite. A discussion between medical doctors/experts may help to firm up the legitimacy of the process behind the prescription and thereby reduce risks if the prescription is followed by the worker. Assuming you receive satisfactory clarification on the worker’s ability to legally possess and use marijuana, practical application of the worker’s rights and company policies in the workplace is the next step and should consider the following questions:

- How have we handled similar cases with prescriptions that impact the worker’s ability to work safely? Review the information you obtained from the prescribing doctor in past cases where workers presented a prescription for a medication with impairment effects. What you experienced may help you craft your initial requests to get what you need in a single document from the prescribing doctor. Lessons learned from the implementation of restrictions in the past can also be instructive. For example, if confusion on restrictions on the part of the worker was an issue in past accommodations cases then the details of that experience may help you to draft an agreement that confirms understanding and agreement by the worker on compliance with restrictions as a condition of being at work. Lessons learned like this may not yield any quick fixes, but may help you avoid pitfalls or false assumptions.

- For the specific job of the worker, does the job description and job hazards analysis adequately describe the safety-sensitive aspects of the job? As with any case where medication presents a potential for impairment, understanding what portion of the job is safety-sensitive is key. If a set of duties that are safety sensitive can be eliminated and leave a meaningful set of tasks then the path for accommodation is defined. Consider providing more details or explaining the work context in a cover letter if the job description or job hazard analysis is brief or generic.

- Do you (and your organization) understand the medical restrictions and have the ability to ensure compliance? For most alcohol and drug policies, the guidance for managing a prescribed medication would also fit with managing a prescription for medical marijuana. An employer can request further clarification on restrictions and should ensure the job and work site are fully explained and the safety-sensitive aspects of the job are presented. A team approach to designing and implementing the accommodations based on the restrictions is recommended to include the Supervisor, Labour Relations or Human Resources, health professionals, the worker and the union.

Once implemented, a supervisor with current training, access to reference materials and support from experts can be expected to manage the case day to day and serve as the eyes and ears of the organization to monitor ongoing compliance.

Scenario Imagine you are a site Labour Relations Officer, who is informed by site security that marijuana was found in the room of Lee, a worker on the site. When questioned by security, Lee provided a copy of a permit to possess and a prescription for marijuana. Site Security has offered to provide further support to you if needed, but has turned the file over to you. After reviewing Lee’s records, you contact a supervisor and confirm there is no record with the supervisory team of Lee having a prescription. You meet with Lee in person, where he gives you the prescription and accompanying documentation and tells you the following: I just got back to site and worked my first shift today and didn’t have a chance to talk with a supervisor about this new prescription. My last prescription didn’t have any side effects so I didn’t tell anyone. I guess that made me unsure about telling anyone this time. The prescription says I can smoke one small joint every day at bedtime, but I haven’t even done that yet this rotation. You also read in the prescription that the marijuana in dried plant form is to be obtained as per the permit to possess guidelines set by Health Canada. The restrictions and warnings document attached to the prescription also says the patient should be aware of an impairment risk and should not operate machinery or vehicles and should avoid heights as the daily dosage represents an ongoing risk of impairment.

So with this information in hand, what needs to be explored further?

The first concern is the failure to disclose the prescription. If your employer in this case has adopted the Canadian Model v5.0 2014 as a workplace policy, then the employee has violated the Alcohol and Drug Work Rule by failing to notify a supervisor that they are taking a prescription drug that has potentially unsafe side effects. The employee also violates the Rule by working unsafely as they did not disclose the restrictions and could therefore not be following restrictions.

The second concern would be determining what if any other violations have occurred in terms of using the drug. He stated that he did not smoke today, but has he smoked on any other day recently? Also, is he using the marijuana exactly as prescribed and did he obtain it according to the prescription and permit to possess requirements? If the marijuana was obtained in town nearby though an illicit source, that would violate the Health Canada to obtain the drug from a licensed source. Taking a medication that is not identical to what is prescribed means the prescription is not being followed.

A third concern would be the level of detail in the prescription. If the restrictions were presented up front by the worker, could they be implemented safely? Consulting with a medical expert can identify gaps and help to avoid pitfalls in the application, especially for a first-time contact with a marijuana prescription for a worker in a safety-sensitive position.

A fourth concern is Lee’s doubt about the need to report the prescription. A review of training materials and signed documents on understanding the rules for prescription drugs is important. You need to verify if the employee was informed of the requirements and aware of the overarching general safety tenet to ask questions and confirm rules before beginning any work. You may also want to have conversations to confirm if there were any practices at the worksite that ran counter to the training and the policy. This is because confusion created by workplace practices that do not comply with policies can impact the culpability of the worker. In the scenario, with several policy violations uncovered the investigation needs to be taken to completion. Assuming the violations are founded, the employer could consider disciplinary action, or potentially even termination if the worker’s actions were particularly egregious. In addition, the site owner may also issue a notice of a site ban to the worker to protect their interests in ensuring safety on site.

Avoiding pitfalls in managing workers with a prescription Regardless of how or when the issue finds its way into your workplace, here are a few ways to avoid pitfalls when managing a worker with a marijuana prescription. Keep policies, training and reference materials updated. Update your policies, training and reference materials used by frontline staff and managers to ensure they are as current as possible. Outdated terms, the assumption that marijuana is illicit/illegal in all cases, and the wording around drug paraphernalia are just a few of the areas that may need updates.

It may be frustrating to think that you may be one court decision away from needing to update (again). But, your footing is solid if your organization is as current as possible on policies and practices and the only adjustment is in response to the most recent legal change.

Know the site access implications when a new hire presents a prescription. If the case you are handling involves a separation of the roles of the site owner, contractor and employer, then site access rather than the employment relationship becomes the first pinch point for prescription marijuana. Perhaps your policies take prescribed marijuana into account, but the site owner’s policies determine site access. In many Canadian jurisdictions, a site owner has much more legal freedom in its decisions on-site access than does an employer managing an employee with a legally prescribed medication. Once site access is denied a condition of employment cannot be met by the employee and the employment relationship typically ends (unless there are other positions available within the company for which the individual is qualified, especially with a tenured employee). Talking through changes and grey areas with your site owner and partners is essential.

Know the initial steps and questions when presented with a prescription for marijuana. The consistency of case management will improve if you standardize what an employee is told and what is requested in the event a prescription for marijuana is presented. A well-designed document and a matching outline for supervisors on providing info on the work environment and job duties is an important component as well. That way you can spend your time on the most challenging parts of the case, rather than trying to create a checklist, or needing to update job descriptions and a job hazards analysis on the fly.

Be aware that a worker may be experienced in presenting a prescription for medical marijuana. Another observation, in over 50% of the files handled directly by our Practitioner, the subject employee had previously been intervened by another contractor for this issue. In every case of prior intervention, it was mishandled. For each of the mishandled files, human rights settlements compensating for back wages and damages ranged from the high five figures to just under the $200,000 range. This essentially made the individuals sophisticated with high expectations, watching very closely how the company was going to respond to their situation. Being prepared in general terms as outlined in the points above and then seeking expert advice during the process you are best equipped to deal with the experienced worker.

Tread carefully. Leave the medical issues to the doctor, but ensure that the doctor is informed. As you start to consider the practical implementation of the restrictions, answering many of the questions that arise remains the doctor’s responsibility, hence the need for an ongoing interface. When, where and how the marijuana is consumed should be outlined by the doctor first. Once these parameters are set, accommodations can be fined tuned in order to manage perceptions and the impact on a safety culture if a worker will be consuming marijuana on duty or on-site.

As there are no established protocols for dosage (Health Canada stated in March 2014:http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/alt_formats/pdf/marihuana/med/daily-quotidienne-eng.pdf) the restrictions placed on usage become all the more sensitive. There should be plenty of caution with dosages when the drug is first prescribed. Health Canada cautions that there will inevitably be less scientific rigour behind the dosage permitted than behind medicine dosages determined through medical study and subject to regulatory review.

Define best practices for working in a legal grey area. Part of the communication across the organization must be that prescription marijuana is an evolving legal issue. Your staff and organization do not have a fully fixed picture because there are legal precedents and changes yet to come that may change your policies and practices. Many people struggle with the grey area this creates for enforcing policy compliance and ensuring safety in the workplace. In particular, leaders in safety-sensitive operations often have a strong and understandable bias toward safety factors. And when there is doubt some err on the side of safety, medical accommodations and privacy rights take a back seat. Prior experience has taught many supervisors that messages are best received when they are black and white and the subtleties of this type of file can be easily lost or dismissed in the workplace. However, the need to balance these obligations should be emphasized. This is part of the tough reality of managing issues that force decisions to be made in the grey area where accommodations and safety meeting. Emphasizing critical thinking in front-line decision-making is key. Second opinions, current training and resources and pausing (even if only for hours or minutes in some cases) can have a big impact on the outcome of workplace management of prescription marijuana issues.

Conclusion Regardless of how or when the issue finds its way into your workplace, here are a few ways to avoid pitfalls when managing a worker with a marijuana prescription. Keep policies, training and reference materials updated. Update your policies, training and reference materials used by frontline staff and managers to ensure they are as current as possible.

Recent Comments